I first encountered the work of Eleanor McCaughey in 2015 when I saw her solo exhibition Image is Everything in Dublin’s Eight. There McCaughey collated and presented an Americana she had fictionalised using found photographs that depicted American diplomats and their families during the Cold War years. In that show hints existed to the new shift in direction her practice was about to take, and in the intervening years I voyeuristically watched this evolution through social media – peppering it with real life contacts at various exhibition openings. It was at one of those recent chance meetings in Pallas Projects + Studios, where McCaughey is due to present a new body of work later this week, that we, having also discovered that we had recently become neighbours, decided to formalise one of these chats over some tea. While on a weekend away in Cork I scoured a tea shop and settled on an afternoon Indian Chai. Shortly after, we met for a late afternoon cup to chat about Eleanor’s new work, how she arrived at it and her plans for the future. Below is an extract from that conversation.

***

Your 2015 show Image is Everything saw you take found photographs from the 1950’s and ‘60’s to create a cohesive anthology of paintings that depicted Americana in the decades succeeding the Second World War. You accompanied that show with a pair of 3D paint sculptures, created from a variety of materials but finished in paint, and a style ‘looser’ than that of the paintings. When I look at your latest work it’s quite easy to back-trace it’s genealogy to these two sculptures. How accurate is that assessment? And can you talk a little about how those sculptures came about?

We were chatting about this in Pallas the other day. A few of the photographs that were used in Image is Everything I had found in France, in a kind of market-style car boot sale. A lot of them were of government meetings but they also showed the after-parties to these meetings. While I was in France I also saw lot of Toulouse-Lautrec paintings, and I loved the colours he was using, the viridian green that was popular in Paris around the time of absinthe. I started to use these greens in the faces, and because I was painting from black and white photographs I made up the colours. The paintings started to become looser, more abstract as I was experimenting more with colour. This saw the strokes get looser and the colours brighter, I just wanted to capture them in 3D form. I wanted to paint the sculptures as I had painted the shadows in the pictures but I wanted to do it on a 3D Surface. That’s where the sculptures came from, that idea. I wanted to bring the paintings alive and I know that sounds a little ridiculous!

All the feminists – oil on board, 2015

In 2016 your work began to take on the recognisable form it has now, with the emergence of these lush sculptural bust portraits. The first examples, especially Toast and Cian, are still quite pictorial and it isn’t until later pieces like Figure 8 that we see the more established setup you currently use. How did those first sculpture paintings come about, and what spurred the shift to a full bust?

In my head I got sick of using found images. I was pulling photographs from the internet and those images can crop up somewhere else – they weren’t mine. I wanted something really original to work from, and as well that’s why I started thinking about painting the sculptures because it would be an original image. At the time I was looking at Francis Bacon and I liked how there was still abstract parts of the face. His work isn’t detailed in a traditional sense.

Like his Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer?

They’re gorgeous! Bacon used found photography but he would also paint something and drop it to the floor – adding it to the mess, walking on it, paint would be dripping on it. It would be a complete mess, but months later he would pick it up and it would have creases and stains, which would totally change the image. I wanted my own image to work from so that’s why I started this crazy process where I would take a found photograph make a painting of it, like the old work in Image is Everything, but now I would isolate a figure and make a sculpture of it. I would then go back to the original photograph I found and collage it with a photograph of the sculpture and then paint it. Maybe it was because I was afraid to go completely abstract, I was trying to hold on to the figure a bit.

Cian (l) & Figure 8 (r) – oil on panel, 2016

But then you loosened the process a little?

Then I ditched the end of it, and ended it at the sculpture. Now I don’t even use found photography I just make them up. They’re very abstract now, but in my head they make sense.

At no stage does it feel like a separate artist, they’re a progression of your work. When I look at the most recent pieces you’ve completed, Invisible Emperor, Sleazy Listening and Typhonian Highlife, a flamboyance exists that speaks of a confidence and comfort with the work.

I’m definitely more comfortable with the work. I think this comes from the source material and the fact that it’s mine. I can experiment and push it as far as I want. I feel that with this work there are no copyright issues. Even if it was a found photograph in my family’s photo album I’d still feel like it’s wasn’t mine. When I studied animation there were all these people in the class that could make stuff up in their head and I just really found that fascinating as I have to copy stuff. That’s why it was new to me to make up this sculpture from my head, but there is also still a layer of copying as I’m still painting the sculptures, it’s still quite technical.

I read a description of your work as “an amalgamation of still life, sculpture and portraiture”. In essence all are the same in what they depict, but the mode of transmission and the weight of the message they deliver alters what they depict – this alteration is partly controlled by the artist selection but also by the audience preconception of what that art form is. Is this amalgamation a look to dissolve and shift the boundary walls between the trio?

They are all three, and I’m not challenging that. I’m just laying it out there and it’s completely up to the viewer. To me they’re portraits. When I started painting it was all figurative, then I got into portraiture and started doing commissions for people. I have always gravitated towards the figure, always. I know the viewer might look at them, especially the newer work, and they might see an abstract object but in my head they’re figurative busts. For me, and I know this is ridiculous, there is no difference between them [gestures to a painted portrait of man across the room] and that [points at an image of Invisible Emperor], because in my head they’re both figures. Sometimes I like that the figures, the sculptures, are really abstract but that you can still tell it’s a head, or that’s hair – well it could be, it might not be.

Invisible Emperor (l) & Typhonian Highlife (r) – oil on panel, 2017

To me your work seems a comment on the modern take on sculptural busts. Modern painting has gravitated towards newer types of expression but we haven’t necessarily assessed sculpture in the same way, we don’t commission sculptures at the same rate that we used to so we don’t engage with these mediums as often. Your work is a return, in a way, to these traditional art forms and the modes of transmission for portraiture. If a sculpture is a representation of someone, but then so is a Picasso without necessarily looking like that person then why can’t a sculptural bust that doesn’t technically look like a person still not capture that same essence?

We are in the selfie culture and people are obsessed with taking photographs of themselves, and they’re portraits. I just love how tacky the culture is, and I like expressing how tacky that is. I’m really into fashion and I buy Vogue every month. It’s a huge influence in my work via the colours and the patterns, the collections at the moment are filled with clashing patterns. I grew up and became a teenager in the 1990’s, and that era, along with the 1980’s, became a huge influence on my work. TV shows back then had all these patterns, like Saved by the Bell which had all these zig-zag and diamond patterns in the graphics, even in their clothes. Music videos had all these neon backdrop through green screens as they danced in front of it. All of these things become influences, I guess it all is really.

Do you have plans for future work with the sculptures themselves?

It’s a tough one. I feel like my sculptures are my source material, they are to me what those found photographs were to the old work. I really don’t know if I should show them or not, well not for the moment anyway. It might be feeding the viewer too much, a little bit literal.

You’ve adopted a larger size recently. Have you up scaled the sculptures?

No, there still tiny!

How much of a difference have you found with the larger format?

I don’t have a studio anymore because of the rent and at the moment I’m working at the house. I always swore when I left college that I’d go smaller and stay smaller, because lugging around my degree show was a complete nightmare. I had massive installation of wooden shapes as well as these massive paintings and I don’t drive! So I had to call on my brother and I thought “I’ll go smaller now! Fit it all in a bag, and head down to the gallery” but it’s kind of boring. I’ve definitely upscaled, at first I wasn’t sure they translate well into large scale paintings because the sculptures are so small. But I think they work, there even more gaudy!

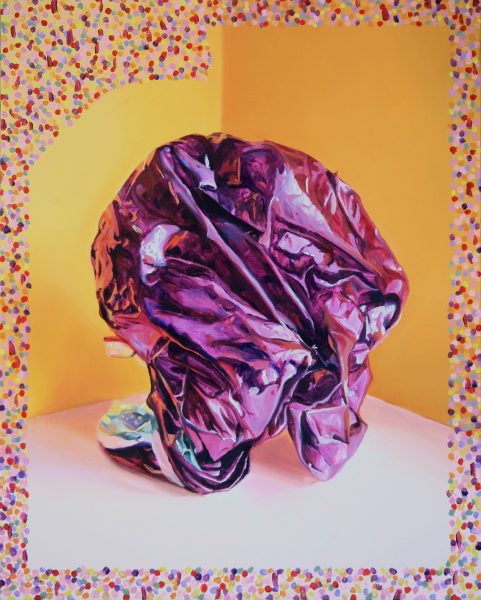

Decoration – oil on Canvas, 2017

What are your plans for the future?

The big thing on the horizon is my new show There is a policeman in all our heads; he must be destroyed which opens in Pallas Projects + Studios at the end of the month.

From chatting today, it’s clear you’re still at the genealogy of this project. That’s the thing that’s most exciting – to see where it goes!

It’s still only a year old, I only started the first one last April.

***

As the conversation draws to a close we begin to google the random oddities that popped up during our discussion. The rabbit hole of results is filled with the wonderfully garish and tacky; and sees us watching some Estonian hip-hop in the form of Tommy Cash’s WINALOTO. As I leave we note that our next random meeting won’t be so random as Eleanor fills me in on the opening night for her show. She advises that she has some pieces to finish but preparations and plans are well under way. I wish her well and eagerly anticipate the results. With her new body of work McCaughey has begun an intriguing exploration into the process of portraiture, this next body of work is a comma in that discussion rather than a full-stop – and there is no rush to find out when that full-stop is.

Eleanor McCaughey’s There is a policeman in all our heads; he must be destroyed opens in Pallas Projects + Studios on Wednesday August 30th and continues until September 2nd – more information available online here.

Title Image: Absinthe hour – oil on Canvas, 2017

***