This text was originally published in Issue #1 of OVER Journal

Aidan Kelly Murphy on experience art in this ‘New Normal’

In mid-March, my inbox began to fill on a daily basis with emails containing various takes on now familiar phrases: “In these unprecedented times”, “In these uncharted times”, “In this new normal”. It seemed as though every company, art institution, record label, and spambot had found the perfect ice breaker to crack that difficult first paragraph of a pitch. What had begun as a temporary lockdown, escalated to the closure of huge swathes of society. As the days turned into weeks, it became apparent that we needed to shift our thinking to reflect the long-term solutions being proposed, and begin considering timeframes in terms of months and years. Soon a new type of mail began to trickle through: the online viewing room email. We were now looking at a long-term, socially-distanced society. This would have acute impacts to the industries of tourism, hospitality, and the arts, alongside the multitude of regulations and guidelines that they and other industries would also need to adhere to. This development brought with it new considerations about when, where and how we interact with art that weren’t immediate concerns when the lockdown was framed as a two-week protocol.

On a personal level, I began to worry about what this change would have on my relationship with art. On Zoom calls with friends, the marginal improvement to our mental health from the near eradication of social FOMO was joked about but also taken somewhat seriously. For me, the retreat of this social FOMO coincided with the advancement of another: arts FOMO. In the ‘Before Times’ I didn’t have to worry about what was on in New York or London. I had looked on with a small bit of jealousy, but I wasn’t actively upset about my inability to physically see the show—I was outside of it, it had no agency over me. Now that it was a viewing room, how many could, would, and should I get through in a day? Was I to spend my morning in Liverpool, Rotterdam or Rome? Post-kids’ bedtime was I expected to spend hours on Issuu looking at catalogues and books? Art had always been omnipresent in my life but in a comforting way, and the lines between it and my personal life were clearly demarcated. Now both, along with my work life, we’re all swirling around together demanding attention that couldn’t be as easily discounted as it had been pre-COVID. To help process this flood of emails I began to quickly scan each, looking out for three criteria to better inform my decision as to whether I would engage or ignore: was the medium conducive to a worthwhile digital-only experience? Was the artist someone whose work touched on digital realms, and, as such, would this presentation enhance their work? Was the institution contacting me one that has previously engaged in this way or was already set-up to facilitate a positive digital-only experience?

Caravaggio’s Medusa, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Ongoing

To help answer these questions, I began to assess them using the concept of a “hierarchy of experience”; there are many different theoretical versions that explore this concept, but most can be summarised into two separate states: basic needs and higher needs. The first state, as the name suggests, are a user’s basic needs, and focuses on the core building blocks of a user’s experience: Is it functional? Is it reliable? Is it easy to use? The second state elevates an experience, focusing on aesthetics, convenience, and meaning. Here, the aim is to ensure a meaningful encounter. Previously, decisions made around engaging with art would be qualified by interrogating the second state. This is because, within the context of the art world, the first state rarely changes. These criteria have been met, in most part, by the building itself. The second state is predominantly left to the curator and the artist, adding layers as they go, hoping to create unique and immersive experiences.

It is these layers that we assess when deciding to visit a show. However, in this new online world, institutions have to lean on their extant digital offerings, which focus either solely on the first state, or contextualise the second state within the framework of a physical exhibition or event existing as well. They were designed to be repositories for information rather than be exhibitions themselves—now they are being asked to be both. As I began to apply these three criteria to the communication I was receiving, and work my way through the email monster that was growing daily, I realised that I was commenting on the layers and outputs of the art world, rather than interrogating the power structures that define the inputs and direction. In essence, I was focusing on the second state without analysing how the first state came into being. In the coming months, decisions on how to adapt to this “new normal” would have ramifications across the whole of the art world that could ultimately steer its trajectory for the next decade and longer. We need to contemplate how things like mediums, artists, users, and institutions operate in the online world to ensure that everyone is brought along equally and fairly on this journey.

Instagram, 18th June 2020 @ 19:53

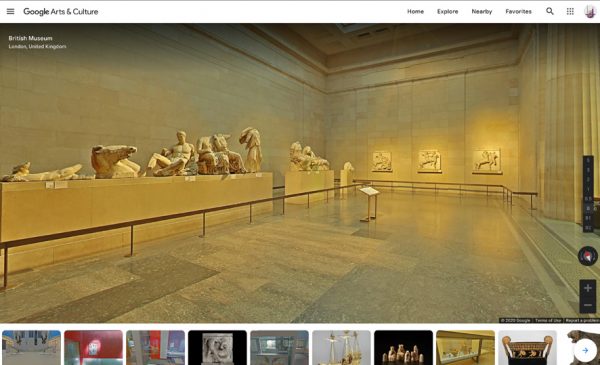

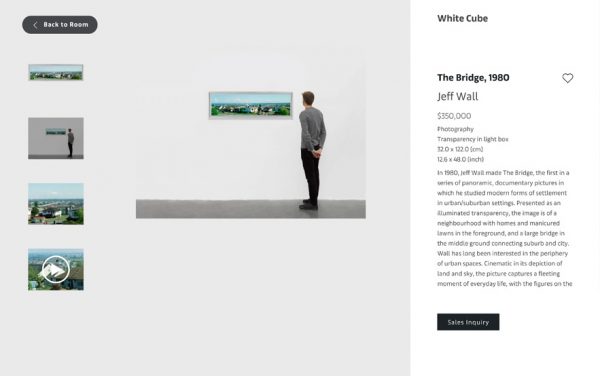

In recent years, viewing art online has become more commonplace; with social media, particularly Instagram, becoming a more frequent access point to engage with an artist, gallery or exhibition. And whilst this mode of delivery can be a poor replica of the experience of physically seeing a show or work, it nevertheless remains a key and broadly welcomed development. In part, this is because these digital- only interactions were designed to provide an opening to, rather than supplement, real-world interactions. During lockdown, and as we continue to navigate our way out of it, these digital- only interactions have increasingly taken on more of the heavy lifting in terms of art engagement. Certain mediums are better suited to online delivery, that is plain to see. For example, lens-based mediums can function outside of the gallery space more effectively than others, with the ability to host online image galleries and videos. And while issues still surround this, mostly notably the fact that artists are required to relinquish control over aspects of presentation that normally would be central to an in-person delivery— colour will be determined by screen calibration, frame rate affected by the users’ machinery, etc.—it still functions at a higher rate than other mediums. Painting loses some of the more tactile elements of the canvas, with sculpture struggling in a 2-D world—as a Friday evening visit to see Caravaggio’s Medusa in the Uffizi demonstrated. Of all mediums, performance art encounters the most headaches having to juggle the logistics of trying to find a suitable location to host their work alongside the loss of direct audience interaction.

Currently, the majority of exhibitions that are being shown online are digital versions of ones already programmed and in some cases installed. As we emerge from lockdown and begin to plan for 2021 and beyond, there might be a temptation to devote the limited space and time that does exist in the physical world to those mediums that struggle in online-only environments. Instead, we should explore digital projects that comment on digital interactions, ensuring that those mediums that already function at a higher threshold online do not end up being confined to that realm only. There are increasing uses of software within the art world, from 3-D printed sculptures to works that have originated from, or make use of, in-game engines. Exploring these elements via online delivery balances the subject and the medium with the delivery rather than just the medium alone.

Room 23, British Museum, London, Ongoing

Utilising digital spaces will alleviate some of the reduced capacity but it will not make up for all of it. If we look at the future problem of reduced capacity and resources through the lens of an existing and similar problem, that of studio and exhibiting space, then we can get a sense of a forward trajectory. Focusing on Dublin for a moment, in recent years we have seen the closure of a number of studios and independent galleries, as the cost of maintaining a space within the city became too large a financial burden—a pattern that is by no means exclusive to Dublin. This resulted in increased competition for the spaces that did remain; and predominantly these have gone to more established artists. The result has been a shutting out of recent graduates from access to spaces to develop their practice and then subsequently show their work. When we look at the solutions already stood-up within the art world since COVID-19, we see that art fairs have been some of the most successful, a trend that naturally leads to a bias for those artists seen as being the most effective in a commercial sense. As these are invariably established mid-to-late career artists, a further hurdle is now in place for those embarking on their career. With space becoming even more of a premium within galleries, it is not hard to imagine a scenario where opportunities are disproportionately reduced for those artists that do not have the same immediate draw on capital as their more commercially viable peers. Therefore, it is imperative that state driven solutions for emerging and mid-career artists are developed.

Jeff Wall, White Cube, London, 19-26 June

In terms of users, the European Group on Museum Statistics notes that expense (42%) and time (29%) are the two main challenges people face in accessing culture. Looking at the impact of COVID-19 it’s clear that these two barriers will not only remain but have the potential to become more challenging in the future. Time and the access to time is raising new challenges within the art world. In recent weeks, we have seen some private and commercial galleries tentatively reopen via appointments. While the ability to return to seeing work is welcomed, it brings with it challenges. On a personal level, time is a commodity that is already shrinking in the world of homeschooling and working-from-home, and while I’m not suggesting that we move to a 24/7 physical art world, additional flexibility for those that do not have it is required. Decentralising more exhibitions and encouraging festivals from capitals and other large cities should facilitate more local viewing and reduce the time needed to travel to see art. Growing up in rural Ireland where exhibitions were hours away, art was consumed via my parents’ magazines and the random subscriptions found in my local doctor’s office. And whilst

the last few weeks have highlighted the journey that online art has taken, it has shown the proliferation of urban centric thinking in terms of solutions.

During lockdown, I spoke with an artist whose work incorporates video and they spoke of the challenges of their work being hosted online, noting that, due to its necessary system requirements, a number of people would not be able to view their work. Art is often lauded as being a democratising force, but loss of access will diminish this claim. We have seen in recent weeks the hierarchies that exist in terms of working, with those able to work from home being advised to do so and those unable to do so being forced to return to work. Future solutions to the current challenges must take into consideration all users. At the start of lockdown, conversations seemed to be of hope, of change, discussions where people voiced that the unique challenges of the current normal would result in nuanced thinking, that in turn would lead to bespoke solutions, with the potential to change how we value things. In recent weeks, this seems to be forgotten as the rush to “get things back to normal” seems to have prevailed, as does the chance to rebalance the status-quo. For the art world the opportunity remains, but it is beginning to slip further and further out of reach.

About

Aidan Kelly Murphy iis a photographer and writer based in Dublin. He has been the Associate Editor for CIRCA Art Magazine since 2019 and the Arts Editor for The Thin Air since 2017. He is a contributing writer for Visual Artists Ireland and London’s this is tomorrow, with his writing also being published by Paper Visual Art, Critical Bastards and the British Journal of Photography.

***

Originally published in Issue #1 of OVER Journal