A feeling of déjá-vu grabs you as you enter Gallery 1 of the Douglas Hyde Gallery. The work of Dennis Dinneen (1927-1985) adorns the walls; encapsulated within these frames is a lost Ireland – and one that we have recently begun to yearn for more frequently. The déjá-vu stems from attempts to join visual memory dots between the scenes and photographs displayed and a familiarity that exists within our own personal memory of our Ireland. While there’s no question it’s Macroom, Cork, it could easily be Cashel, Bundoran or any other town in mid-twentieth century Ireland; Dinneen’s inward facing scenes are devoid of recognisable landmarks or buildings, further enhancing this. This familiarity warms the heart before saddening it, and eventually consoling it. Dinneen, who operated out of a studio adjacent to the bar he and his wife ran, captured intimate and important moments within the lives of his townsfolk. His practice was often accompanied by a jovial humour, evident in the approach he brought to his compositions and framing. Dinneen also served as his town’s taxi driver, completing the triad of the local publican, the town photographer for documents and family portraits, and the transport home for anyone who required it. With this he was the town’s cultural axis, creating the social environment that put his subjects at ease – and one that sets him apart from similar cases. notably Disfarmer.[1]

While in the gallery I overhear a group of American tourists, fresh from the Book of Kells, as they meander around enjoying and interacting with the work. They stop at a portrait of two young women – both in “fancy coats”, on the left a short fringe that has recently returned to fashion, on the right a head shawl and curvaceous glasses. Their initial assessment is that the girl on the lef tis their mother. They analyse the subjects. Encapsulated within this interaction are the layers of recent Irish diaspora: the emigrants of post-Emergency Ireland, the offspring of those emigrants who’ve returned to explore the homeland of their ancestors, and me – a descendant of those who remained, distant from them and detached. Despite our reliance on tourism as an industry, we regularly, and often in a flippant manner, dismiss our North American cousins. Having remained, we question their desire to reconnect with a land they only recently disconnected with, in a physical sense at least. It is here that the somber and respectful sadness emits. The passport photographs, originally cropped to headshot but here enlarged to show the full scene, speak of a generation of separation. Keepsakes of relatives, soon to be seperated by the Atlantic and other oceans, are created and will soon become treasured artefacts. Active through the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s, Dinneen could have photographed a child’s christening, communion, confirmation, adventures on Hallowe’en, hijinks in the bar, before eventually sitting them down to create the image necessary to secure their departure from their homeland; he may have even captured one last image for a momento.

In this exhibition these previously personal photographs, be they for official documents or to rest upon the family mantlepiece, are opened up to a wider audience to engage with. While this results in a multitude of unique interpretations from each visitor, at their core Dinneen’s photographs use the power of a mid-twentieth century visual vernacular of emigration and religious rural Ireland to extract and channel a singular and overarching story of community and family. Each visitor can then interpret their own place within this story and the role it played within the shaping of their own personal and familial history. This allows for a connection, and one that ultimately provides us with a context for the long journeys and tough decisions made by our predecessors. It is here that Dinneen’s work provides us with consolation.

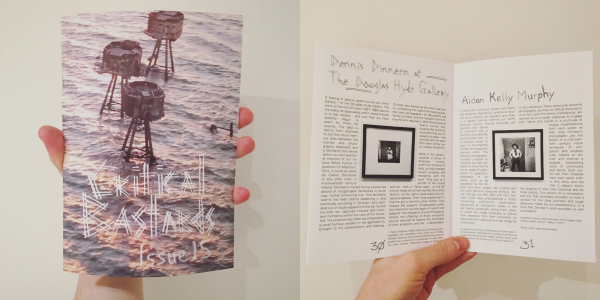

Dennis Dinneen, The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, April 21 – May 2017.

Installation views: Aidan Kelly Murphy

[1] Mike Disfarmer (1884–1959) was an American photographer who operated a town studio out of Heber Springs, Arkansas. Like Dinneen, Disfarmer has received posthumous acclaim for his portraiture of rural America; unlike Dinneen, Disfarmer’s imagery is known for its removal of emotion and employing a stark realism – something that is attributed to his distance from the local social environment and his lengthy sittings, which were often in silence: the antithesis of Dineen’s approach.

Originally published in Critical Bastards Issue 15.