Aleana Egan and Isabel Nolan, Material Flux

Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, 29th June to August 10th 2024

Highlanes Main Gallery

***

A visit to Highlanes Gallery in Drogheda reminds me of the codification of words in religious architecture. It feels somewhat awkward to refer to the former altar as a ‘raised plinth’, more natural to label the two smaller side rooms as chapels. While Highlanes is now a more neutral space, it maintains a residual energy from its time as a religious entity, a time when it was profoundly unneutral. Just as IMMA will forever be a former hospital, The Dock in Carrick-on-Shannon a courthouse, and The Model in Sligo a school, Highlanes will always be a former church. Aleana Egan and Isabel Nolan explore this history in their show Material Flux, looking to ‘nudge, play, and exploit the ways in which religious architecture mediates our encounter with matter and meaning’.1

This mediation is most prominent in the main gallery due to the presence of key architectural features, like the altar and a number of stained-glass windows. The works, in particular the sculptures, engage with this residual energy. Egan’s memory shape, (KG/Highlanes) (2023-2024) – past iterations were shown in Void Derry and Dublin’s Kerlin Gallery – surrounds a column, directly linking it to the building. Its rectangular form, created from six pieces of shot-blast steel, is laid out to construct a three-metre by six-metre frame that houses cellulose fibre (recycled newspapers used for housing insulation). This frame is not welded together, instead it holds its contents together like an embrace that feels like it may come apart at any second. The physical space it occupies is almost exclusively horizontal as it is just three-centimetres tall, drawing you down to the material of the floor. This is a common curatorial trend seen in the placement of works throughout the show. Sculptures are either hung on walls, placed directly on the ground, or arranged in such a way as to provide the artworks with ample room to resonate with the energy from the architecture they interact with.

memory shape, (KG/Highlanes) (2023-2024)

The floor is also where the light, dappled with colour from the stained-glass windows, dances across surfaces, catching the edges of materials. Bissera V. Pentcheva used the phrase ‘material flux’2 to describe the liviness of matter in these sacred spaces – in particular the light cast across surfaces and the acoustic qualities – and Egan and Nolan’s choice of it as a title for the show draws our attention to this visual phenomenon. The positioning of works, with sunlight illuminating different windows and casting different light across the floor throughout the day, speaks to what must have been a long consideration by the pair as to the individual locations of certain works.

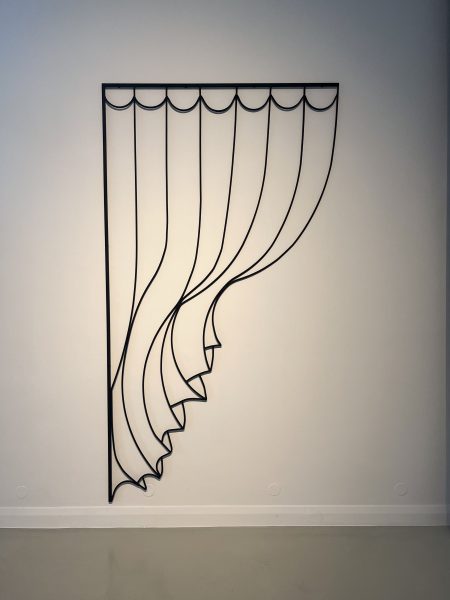

For Elsewhere, 2024

Jagged Resort, 2024

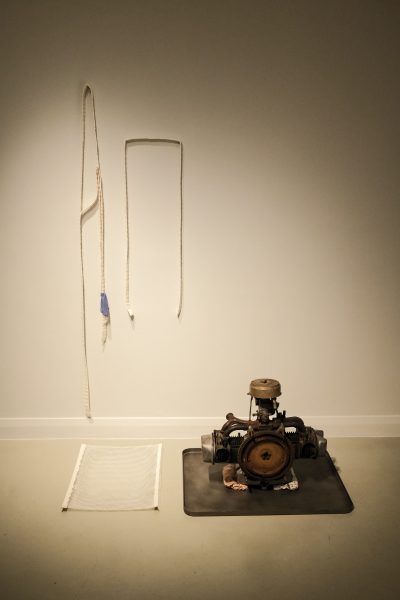

The show contains a number of older pieces, and those chosen carry the narratives they formed in their original shows to Highlanes. Here the space adds layers to their story, and highlights the impact that it has on mediating our interpretation of works and matter. For example, Nolan’s Gas Giant (2012) was shown in IMMA, in 2014’s The Weakened Eye of Day. There it discussed themes on celestial bodies, while here it suggests the spiritual side of celestial realms by transforming into a church banner despite no physical change in appearance – its mutation achieved by the energy of the space. The impact of ecclesiastical energy is also present in Nolan’s Dashing Hopes (2024). Positioned on the old altar with its rope appendages draping down the steps. At first the sculpture resembles a chandelier, looking as though it has come down from the ceiling and is a comment on the fallen grandeur of religious buildings. It’s circular, three-tiered frame is made from 26mm black black steel tubes with ropes of varying thicknesses and colours tangled together. Within these ropes are a number of fish made from fabric, giving it a form closer to a fishing pot or anchor, something less visually appealing than a chandelier, but something of greater use – particularly in a port town like Drogheda. Its placement on the floor accentuating the double height space surrounding the altar, and breaks down any delineation of space between the nave and altar – emphasising the journey the gallery has been on since its secularisation.

Dashing hopes, 2024

Accompanying the five sculptures in the main gallery are five smaller works – four of which are painted, c.50cm x 50cm, and one a photograph. The paintings share a common motif of flowing colours across the surface. Nolan’s patterned elements recall the stained-glass windows, with Egan’s paintings being typified by bursts of colours that resemble celestial bodies moving across the sky. On the back wall, opposite the altar, is Nolan’s Aperion (2024). Alongside shapes of vibrant reds, greens, and blues, are handwritten sentences and phrases partially visible on the surface. Like fragments of disintegrating gospel papyri or Sappho poetry, they sit on top of the overlapping and converging patterns. The work’s title comes from Ancient Greek cosmological theory, with the word aperion seen as a boundless substratum that holds the opposites of the world together. This holding together of the opposite is a sense I get from viewing the exhibition as a whole. The materials in many of the sculptures are contrasted between warm and soft materials (like fabrics and the insulation) and colder more solid materials (most notably the steel).

Dashing hopes, 2024

Animated Summer, 2017

Tucked into the first side chapel are four works, two new and two old, two Egan’s and two Nolan’s. In Revelation (2024), a Nolan watercolour on paper, we see a nod to the final book of the Christian bible (Revelations) and to Byzantine architecture, with the outlines of architectural styles overlaid onto and constructed out of flowing patterns to show a cross-section of the Hagia Sophia. These smaller, more intimate spaces – five foot by five foot at best – have a denser energy and create a contrasting presentation to the larger space. This room also holds Egan’s a cove from the enclosed (2016), a gouache on paper featuring muted blue and vibrant red forms – like jellyfish that have evaded capture from Nolan’s fishing pot, floating across the canvas. Here, eight years after the work was created, we find it in a cove. When thinking of this piece, in the context of the environment it is now presented, I recall Rebecaa Solnit’s essay Grandmother Spider.3 In this Solnit talks to ideas and themes that resonate with both this work and the exhibition as a whole. Her descriptions of male oppression through the lens of a woman’s coverture, and the absence of her separate existence, reminds me of the challenging legacy of these religious spaces – a legacy that isn’t always captured in ornate glass windows. The essay’s opening line, “A woman is hanging out the laundry”, is even more pertinent with the town’s county home, which was frequently used to house unmarried mothers and their children, being only a 10 minute walk away and open until 1955 – only closing after a new mother and baby home was opened in Dunboyne.

Apeiron, 2024

The title for a cove from the enclosed (2016) comes from a letter by Rosemary Mayer, to her sister Bernadette, where she describes local shopping centres.4 In the exhibition we find it around the corner from a work depicting Drogheda’s local shopping centre. The Abbey Shopping Centre is about half-a-mile down the road from the gallery, and almost closed down. Photographer and filmmaker Jack Caffrey was invited by the artists to capture it, and in his diminutive but vibrant photograph we see that each word of the centre’s sign is missing a letter. Today it limps on, serving mostly as an auxiliary car park for the town with only a handful of small retailers still occupying the building. This community space has yet to experience the same regeneration as Highalnes did in the early 2000s when it went from a Fransican Friary Church to a community art space.

Abbey Shopping Centre, 2024

Apeiron, 2024

Walking around Material Flux gives the feeling of being a time traveller, encountering works that you’ve seen before, with the distance in both time and location condensed. The theory of cosmic inflation, proposed by American theoretical physicist and cosmologist Alan Guth in 1980, outlines how, within a fraction of a second, two points in space less than the width of an atom apart ended up millions of light years away during the exponential expansion of space in the early universe. 5 These points in space, and the objects that inhabit them, are forever linked through the cosmos by their energy and heat. This idea of permanent linkage despite the distance of both time and space, is something contemplated during and after visits to the show, alongside thoughts of how these works change energy through their ongoing contextualisation in the spaces they did and now occupy. These links to their past works and the history of the spaces they have and now inhabit, provide us with rich histories to consider and appreciate the works, and an opportunity to speculate how their energy will continue again. They are, as Egan and Nolan advised, ‘valves, flowing through multitudes of thoughts, energies and process[es]’. 6

***

A special thank you to Adrian for his guidance and editing with this text – very much appreciated.

footnotes

- Material Flux exhibition booklet ↩︎

- Pentcheva’s description refers to to the Hagia Sophia – a 4th century mosque and former church and museum in Istanbul – and in an inverse to Highlanes, was, controversially, reclassified as a mosque and not a museum in 2020 ↩︎

- Solnit, R. (2014) Men explain things to me: And other essays. S.l.: Granta Publications. ↩︎

- Mayer, R. and Mayer, B. (2022) The letters of Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer: 1976-1980. Cologne: Walther Koenig. ↩︎

- Dunkley, J. (2019). Our universe : an astronomer’s guide. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press. ↩︎

- Material Flux exhibition booklet ↩︎