This text was originally published in Issue #3 of OVER Journal

Aidan Kelly Murphy discusses themes of mental health and football in the work of Gabriel Andreu

In Ireland and the UK men are three to four times more likely to commit suicide than women1, with suicide being the leading cause of death amongst males under 25 in Ireland, accounting for 1 in 5 deaths2, and males aged 20-34 in the UK, with 1 in 4 deaths3. Whilst many factors are at play in each and every one of these personal and tragic stories, it is often thought that men’s struggle to discuss and articulate their feelings is an underlying factor in this gender gap. It is this topic that forms the genesis of Gabriel Andreu’s Heroes series, a body of work that sees the Spanish artist create composite portraits of footballers. Andreu’s images feature British footballers from the 1960s and 1970s – an era when football teams, and their players, were no longer just sporting institutions but becoming ingredients in wider social identities. In Wexford, the rural Irish county where I grew up, there was no League of Ireland football team and, with options limited, many fans during these decades looked out and across the sea to England for a team. My father and his family were no different. He supported Manchester United, his brother’s home was Highbury, after Arsenal’s home ground, with his sister living in Liverpool’s Anfield – next door to my godfather who lived in Trafford, minus the Old.

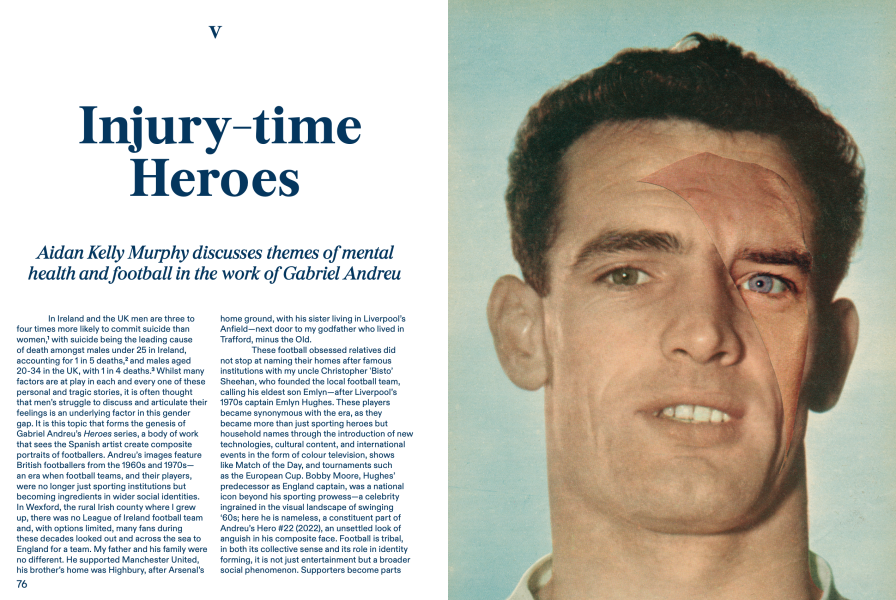

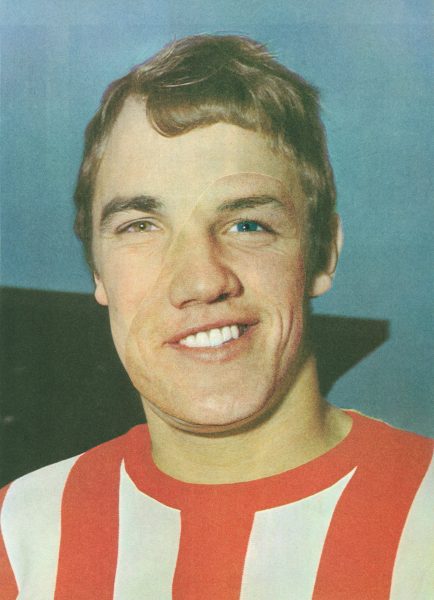

Hero #22

These football obsessed relatives did not stop at naming their homes after famous institutions with my uncle Christy ‘Bisto’ Sheehan, who founded the local football team, calling his eldest son Emlyn – after Liverpool’s 1970s captain Emlyn Hughes. These players became synonymous with the era, as they became more than just sporting heroes but household names through the introduction of new technologies, cultural content, and international events in the form of colour television, shows like Match of the Day, and tournaments such as the European Cup. Bobby Moore, Hughes’ predecessor as England captain, was a national icon beyond his sporting prowess – a celebrity ingrained in the visual landscape of swinging ‘60s; here his is nameless, a constituent part of Andreau’s Hero #22 (2022), an unsettled look of anguish in his composite face. Football is tribal, in both its collective sense and its role in identity forming, it is not just entertainment but a broaders social phenomenon. Supporters become parts of wider narratives, deeper histories that see them take on not just the collective highs but the collective traumas of their tribes such as the Munich Air Disaster, which killed 23 of 44 passengers, and the Hillsborough Disaster which resulted in 97 deaths and 766 injuries. Footballers become outlets for corporeal responses, and in Heroes the trauma, the distress is no longer masked or buried deep. Instead it is to the fore, with its scars visible; the images became simulacrums for processing and discussing personal pain. Vessels by which the reader can reflect their own struggles, in a way that the source materials cannot. They are angst ridden and in distress, they are layered and complex like those that cheer them on from the stands and in front of the television. We can see their masks of masculinity, fixed in place and requiring intense effort and concentration to maintain. These masks also highlight, often due to the culture and construct of the environment they inhabit, the imperfect role models that these footballers are and the anguish they too must feel in adhering to the social construct their sport fabricates and maintains – you can count on one hand the number of professional footballers in the history of the English game who have come out, in contrast to the women’s game where seven members of England’s UEFA Euro 2022 team alone are members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

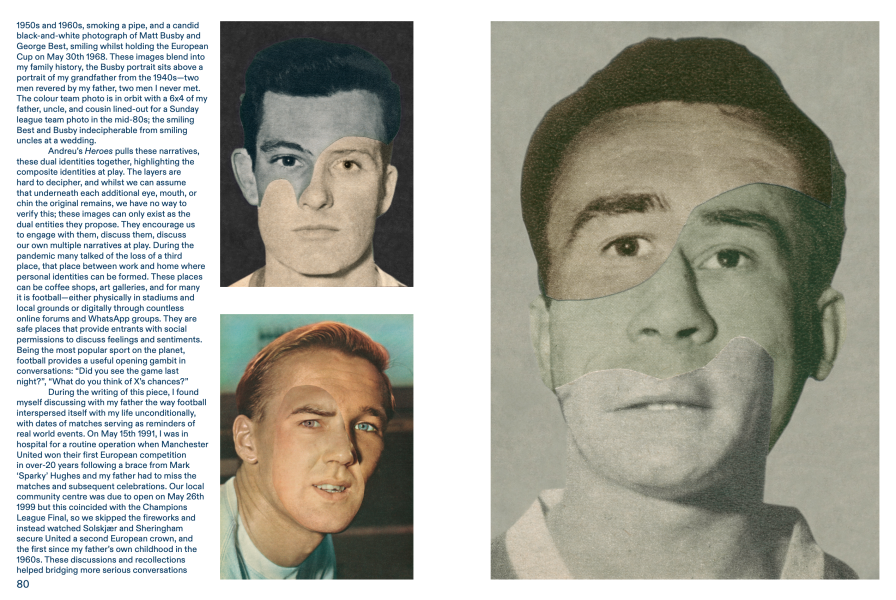

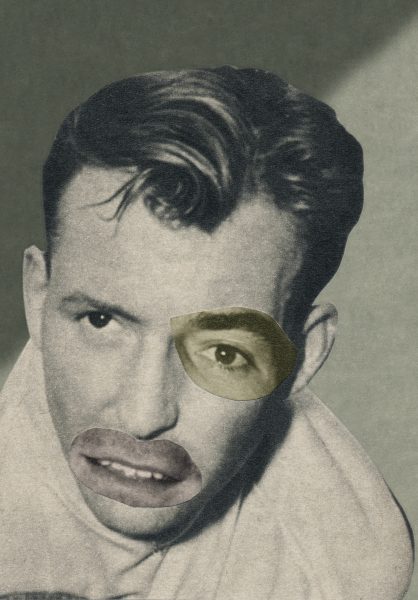

Hero #14

When I was a child I couldn’t escape football – not that I ever tried or wanted to. Its iconography felt ubiquitous and was not just confined to the small screen. Walking down the stairs, and just above your head hangs a small framed photo of the Manchester United crest – I yearned as a child for the day I would be tall enough like my older brothers to touch it. The back of my parents’ kitchen has been filled with images since before I can remember, the imagery bleeding onto the side walls and over the door frames. After running out of space photos, sketches, and other familial paraphernalia were stuck to the front of frames. In recent years, the plethora of images by, and of, grandkids has seen this visual haberdashery grow like ivy and expand across the room and onto the fridge. Despite the struggle for real estate, three large framed images have continued to dominate the left-hand wall, their iconography never diminished. These are the 1966-1967 Manchester United Team photo – in colour. A sepia portrait of Matt Busby, Manchester United manager during the 1950s and 1960s, smoking a pipe, and a candid black-and-white photograph of Matt Busby and George Best, smiling whilst holding the European Cup on May 30th 1968. These images blend into my family history, the Busby portrait sits above a portrait of my grandfather from the 1940s – two men revered by my father, two men I never met. The colour team photo is in orbit with a 6×4 of my father, uncle, and cousin lined-out for a Sunday league team photo in the mid-80s; the smiling Best and Busby indecipherable from smiling uncles at a wedding.

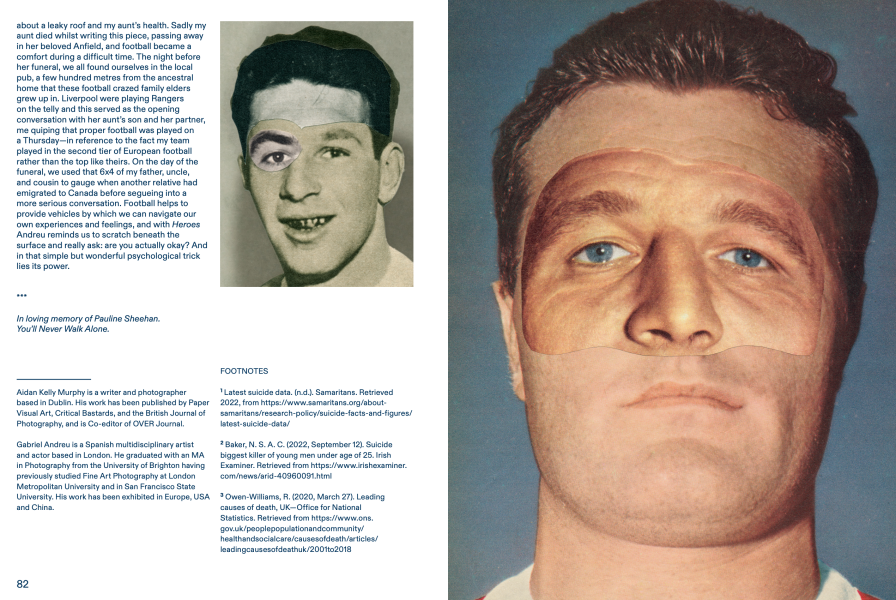

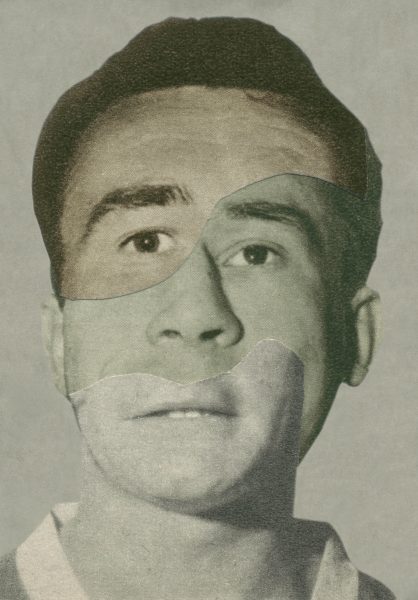

Hero #10

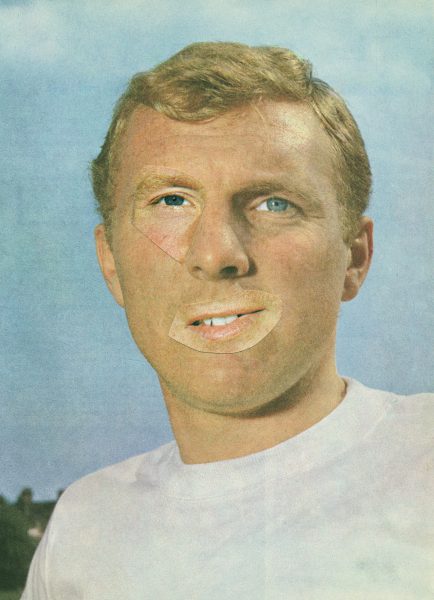

Hero #12

Andreau’s Heroes pulls these narratives, these dual identities together, highlighting the composite identities at play. The layers are hard to decipher, and whilst we can assume that underneath each additional eye, mouth, or chin the original remains, we have no way to verify this; these images can only exist as the dual entities they propose. They encourage us to engage with them, discuss them, discuss our own multiple narratives at play. During the pandemic many talked of the loss of a third place, that place between work and home where personal identities can be formed. These places can be coffee shops, art galleries, and for many its football – either physically in stadiums and local grounds or digitally through countless online forums and whatsapp groups. They are safe places that provide entrants with social permissions to discuss feelings and sentiments. Being the most popular sport on the planet, football provides a useful opening gambit in conversations: “Did you see the game last night?”, “What do you think of X’s chances?”

During the writing of this piece, I found myself discussing with my father the way football interspersed itself with my life unconditionally, with dates of matches serving as reminders of real world events. On May 15th 1991, I was in hospital for a routine operation when Manchester United won their first European competition in over-20 years following a brace from Mark ‘Sparky’ Hughes and my father had to miss the matches and subsequent celebrations. Our local community centre was due to open on May 26th 1999 but this coincided with the Champions League Final so we skipped the fireworks and instead watched Solskjær and Sheringham secure United a second European crown and the first since my father’s own childhood in the 1960s. These discussions and recollections helped bridging more serious conversations about a leaky roof and my aunt’s health. Sadly my aunt died whilst writing this piece, passing away in her beloved Anfield, and football became a comfort during a difficult time. The night before her funeral, we all found ourselves in the local pub, a few hundred metres from the ancestral home that these football crazed family elders grew up in. Liverpool were playing Rangers on the telly and this served as the opening conversation with my aunt’s son and her partner, me quipping that proper football was played on a Thursday – in reference to the fact my team played in the second tier of European football rather than the top like theirs. On the day of the funeral, we used that 6×4 of my father, uncle, and cousin to gauge when another relative had emigrated to Canada before segwaying into a more serious conversation. Football helps to provide vehicles by which we can navigate our own experiences and feelings, and with Heroes Andreau reminds us to scratch beneath the surface and really ask: are you actually okay? And in that simple but wonderful psychological trick lies its power.

***

In loving memory of Pauline Sheehan.

You’ll Never Walk Alone.

about

Aidan Kelly Murphy is a writer and photographer based in Dublin. His work has been published by Paper Visual Art, Critical Bastards, and the British Journal of Photography, and is Co-editor of OVER Journal.

Gabriel Andrew is a Spanish multidisciplinary artist and actor based in London. He graduated with an MA in Photography from the University of Brighton having previously studied Fine Art Photography at London Metropolitan University and in San Francisco State University. His work has been exhibited in Europe, USA and China.

***

Originally published in Issue #3 of OVER Journal

footnotes

- Latest suicide data. (n.d.). Samaritans. Retrieved 2022, from https://www.samaritans.org/about-samaritans/research-policy/suicide-facts-and-figures/latest-suicide-data/ ↩︎

- Baker, N. S. A. C. (2022, September 12). Suicide biggest killer of young men under age of 25. Irish Examiner. Retrieved from https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-40960091.html ↩︎

- Owen-Williams, R. (2020, March 27). Leading causes of death, UK – Office for National Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/articles/leadingcausesofdeathuk/2001to2018 ↩︎