Sven Sandberg: They went and saw a palace hanging from a silken thread

Rathfarnham Castle, Dublin

1 March – 13 April 2020

Review by Aidan Kelly Murphy

Rathfarnham Castle was, and remains, the original hosting space for Sven Sandberg’s solo show ‘They went and saw a palace hanging from a silken thread’. Currently, it can only be viewed online as the space, along with Ireland’s other cultural institutions, remain indefinitely closed. Presented by Berlin Opticians, a primarily online gallery that operates a nomadic lifestyle in the physical world, often occupying historical buildings, images of Sandberg’s works can be viewed alongside in-situ documentation.

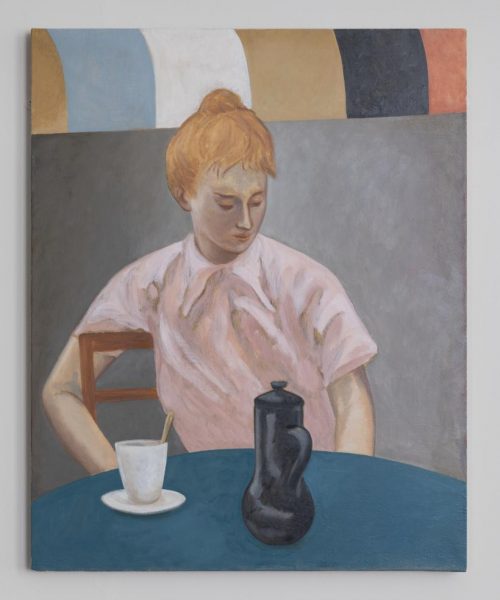

Sandberg presents eight paintings, all of which are oils on linen of varying size, that see him return to portraits of individuals after a brief flirtation with group compositions during his last exhibition as part of the RHA’s Future series. Four of the works are head and shoulders portraits of women on pastel backgrounds, an additional two are of patrons of establishments (a café and a salon) with the remaining two featuring the only male characters: one reading and one outdoors. The works themselves are placed on what would have been the castle’s entry floor. Through the grand entrance hall is the dining room, which houses the four head and shoulders portraits. The saloon, also known as the long gallery, sits alongside both rooms and is where its namesake ‘The last salon of Madame X’ (2019) sits. The remaining three paintings can be located in two squat reinforced rooms that reveal the original defensive nature of the castle, the Pistol Loop room and the Flanker Tower Room. Each painting is hung on a stand-alone white cuboid rather than the walls, which are in varying degrees of restoration, enhancing the museological aspects of both the works and the exhibition.

Sandberg’s cast of actors are drawn from the early half of the 20th century, with a particular focus on the inter-war years. The accompanying text advises that he has tapped into the ‘20s for its atmosphere and the ‘30s for its more demure tones, and here we can see Sandberg’s usually vibrant colour scheme take on a more sombre outlook, though it remains lush in output. He leaves his audience with breadcrumbs to the inspiration behind these paintings, from the cafés and salons of Paris, and John Singer Sargent’s ‘Portrait of Madame X’ (1883-84), to the emergency of Hollywood film and its competition with European theatre. And while these point to cultural references and epicentres, the works evoke a sense of foreboding, as though their subjects sense the fate that awaits them.

Website : https://www.berlinopticiansdublin.com/sven-sandberg-they-went-and-saw-a-palace-hanging-from-a-silken-thread

The ‘20s pose a tricky subject matter. Whilst it is the decade of bohemia and the explosion of art trends and films which make it ripe for source material, actions taken during the decade had ramifications that are still being felt today. The decade opened under the shadow of the First World War which sparked a period of consumption and urbanisation, two factors that are often linked to the Wall Street Crash that went on to define the ‘30s via the Great Depression. Sandberg tackles this topic by presenting both aspects of the decade’s history: the decadence and its subsequent decline. We see characters that symbolise the revelry, but Sandberg pulls his punches in terms of his palette choice to add to the sense of apprehension.

Rathfarnham Castle was once a fortified house in the countryside, now it sits squarely in suburbia, encircled by roads, parks, housing estates and a golf course. It is trapped by modernity, recontextualised by its changing surroundings like the characters of Sandberg’s paintings. Their placement in a grand historic house, which has seen its lustre disappear as the decades turn into centuries, adds a layer of symbolism to Sandberg’s work. And while their current lockdown in the castle robs us of the ability to view these paintings in the natural light, it adds an additional element: they are like us, confined and distant. They wait patiently for an audience that may not glimpse them in person again.

***

Originally published by this is tomorrow, view online here.